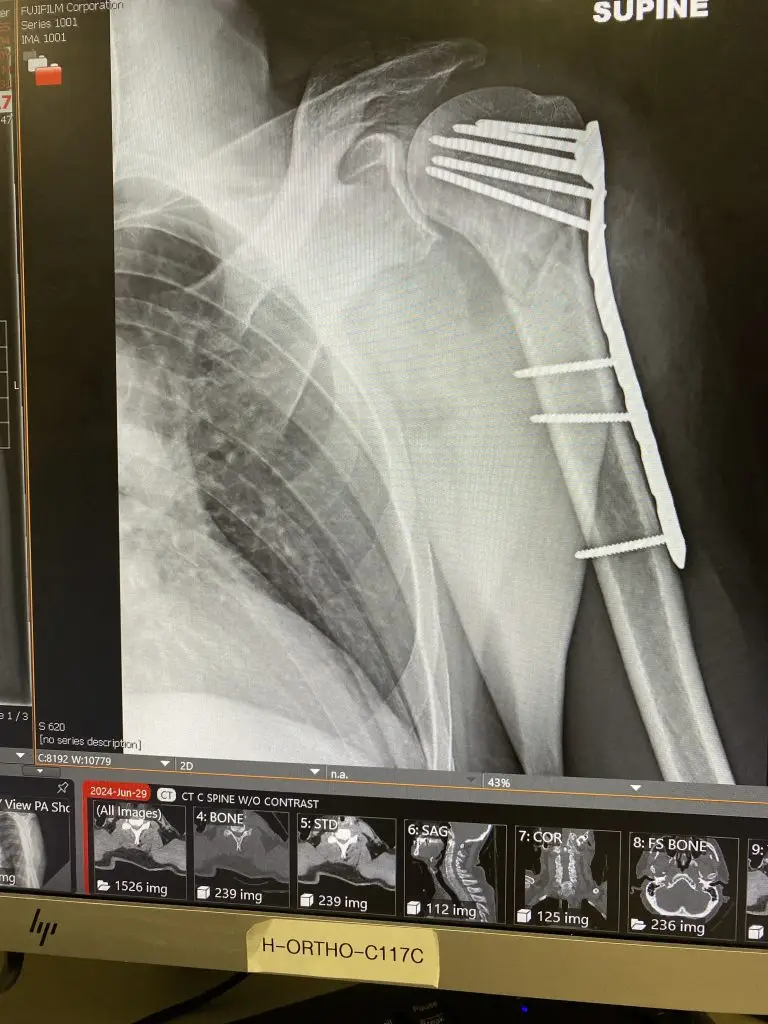

2024, for me, was the year of my first major interaction with the United States’ interpretation of “health care”. My year started in August of 2023 when I stepped on a screw and ended in July 2024 with a piece of metal from the landing gear of an A380 being attached to my broken humerus with screws more typically associated with deck construction.

Part I of this great story was detailed in Gravity’s Rainbow where fate found me and my barely attached left arm at midnight of June 30th, stoned on opiates, but taking up valuable space that could be used for another, better insured, patient.

That part ended with their kind offer to call me an Uber.

I walked them through the details of my night with what little clarity of thought I had, given my cocktail of drugs emulsified by extreme pain, and suggested their plan had a few holes in it. Luckily, regardless of my cognitive circumstances, I can draw on a tone of voice that suggests I don’t need my lawyer’s number on speed dial because I know it by heart.

“Fine.” Harrumphed would be the operative term. “But we’re going to have to put you in the hall for the night.”

“Put you in the hall for the night” is hospital-speak for discharging you without allowing you leave the premises.

I knew this might be my fate because this was not my first rodeo in my Year of Living Carelessly.

In January when my screwed-up foot was giving me issues, I had symptoms that the after-hours consulting nurse at my “healthcare” provider described as “go to a hospital right now and don’t drive yourself”. Off we rushed, to the brand new, still shiny, well-lit beacon of modern medicine in Silverdale, Washington. I walked into the ER, checked in, and took my seat in the near empty waiting room. Safely ensconced in the warm embrace of science-backed “healthcare” I had a moment to take in my surroundings.

Why are there so many cops?

Unfortunately, my name was called, and I never got to answer my question. Tests were run. X-Rays were taken. Doctors were consulted. And, in short order, my case was diagnosed.

“We can’t find anything wrong with you. Take two of these.” He handed me a little envelope of Naprosyn. “And let us know if it gets worse.”

I kid you not.

A few days later, as you may have guessed, I was back in the ER but it wasn’t the easy-peazy experience of the first time. Scattered about the waiting room – standing, sitting, or lying on the floor – were people whose very existence hinged on a recent dose of Narcan. Each was accompanied by a police officer to make sure they got the needed observation, treatment, and subsequent booking.

Ah… That’s why.

A couple hours later, my name was finally called and I was ushered back into a treatment space where more tests were run, more doctors consulted and, once again, there was no actual answer.

“We think you have cellulitis.” (An infection of the deeper layers of the skin, in case you were wondering.) “But can’t really find anything wrong.”

“That’s reassuring,” I recall saying. “What’s next?”

“Well, we’re going to move you into the hall to free up the exam area.”

It being well past sunset in the Pacific Northwest’s January – so, like 4pm – the hall they moved me into was dark as a crypt. Either by intent or malfeasance there was no light in this area. However, I was able to sit there in complete anonymity and listen to the goings-on around me.

And get a glimpse of how screwed up the system really is.

In the bed nearest mine – well lit, I noticed – an elderly man and his wife were awaiting test results. When the doctor arrived, the news was not good. The man had an advanced cardiac disease of some kind and needed to be admitted to a cardiac specialty hospital. The only one that had a – yes, a, singular – bed available was in Tacoma.

A brief aside. There’s a very old joke about a contest where the First Prize was a one-week, all-expense paid trip to Philadelphia and the Second Prize was a two-week trip. Learning that your heart’s future was to be determined in Tacoma would be the equivalent of learning you came in third in that contest.

Anyway, having just been told that he was dying, the doctor then stressed the importance of a quick decision. He stood there waiting. I believe I heard his foot tapping impatiently, but it may have just been the air conditioner failing.

The couple discussed this quietly for a few minutes.

“Okay, we’ll head right over. It will give us a chance to pick up some things at the house.”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“You need to go in our ambulance. Otherwise, you lose the bed.”

“Why?”

“If you take the ambulance, you stay in the system, and you’ve got the bed. If we discharge you to allow you to go home, you’re not in the system anymore and you start from scratch.”

“But we can get a new bed?” The man’s wife asked quietly.

“Two weeks.”

Still trying to get their heads around the “you’re dying” part of the conversation, the couple gave in.

The doctor left, the hallway quieted down, and the couple started talking about logistics.

My story ended when the doctor came up to the bed, smiled, and said, “Oh, there you are. We’ve been looking for you.”

“We can’t find anything wrong but it’s clear that there’s something wrong.”

Thank you, Captain Obvious.

He handed me an envelope of pills.

“Take two of these a day for a week and let us know if it gets worse.

This time, the medicine – doxycycline – did its job and my mystery, Thai-Jungle-Pond bacterium succumbed to its effects. Cleared for travel, I boarded an airplane, rented a motorbike, and headed out – to the jungles of Thailand.

Several months went by and we are now back where this post started. Arm broken, I am wheeled out into the hallway to wait for dawn. I look around.

Wow! Even more cops!

Seattle, being a larger city than Silverdale by several orders of magnitude, experiences a higher level of general criminality as well. Here, though, it was more than just rescued junkies being escorted. Any potential involvement in or, apparently, being nearby a crime scene gets you a free trip to the ER and a police escort. Plus there’s the …

My observation was summarily interrupted.

“Hi, I’m Dr. Kim.”

I bet your mom’s very proud.

“She is.”

Whoa!

“I wanted to let you know your treatment plan.”

“Okay, great! What’s the plan?”

Dr. Kim tossed me a bottle of painkillers.

“Take a couple of these if the pain gets bad. Otherwise, just call us if anything changes. Here’s your appointment for a follow-up check.”

He handed me a stack of paper.

“But this is three weeks away.”

“Yup.”

And he was gone.

And that, in both my experience and that of the elderly couple, is the essence of how the American “healthcare” system works. We, the patients and our families, exist for the benefit of the system. We keep it full. There is no surplus of resources to make sure that everyone who needs treatment can get it. There is no commitment to making sure there are enough doctors, nurses, and support personnel to make that happen. Rural hospitals are being shuttered. The system is cranking out more dermatologists than general practitioners. And, in cities big and small, the hallways have become treatment areas.

All because of money. The US system is managed for cost control. An empty bed represents a cost that can’t be recovered. An idle nurse or doctor, the same. Regardless of your insurance or ability to pay, the system has evolved to make it a better financial decision for them to turn someone away or, my in personal experience, make them wait three weeks with a broken arm, than it would be to have a spare bed or two and the personnel to support it. Just in case.

The United States, for 2025 mid-year, is ranked 39th in global health care. (Down from #36 when I was with the Zombies of Costa Rica fifteen years ago.) But it is still Number One in costs. My new home, Thailand, is 10th, at about 20%-25% the cost, less if you use the state hospitals. When I call for an appointment here, I mostly get “we can see you tomorrow.” It’s never “we’re booking for the middle of next month.”

The difference is all about who the system is set up to serve. When I need it, like I did last year, I’d prefer a system that’s there, ready, and waiting.

Just in case.